Just as vividly, the race showed that only one party — the Democrats — appears willing to grapple with the implications of campaigning under its unpopular figurehead.

In Pennsylvania, Mr. Lamb, a 33-year-old former prosecutor from a local Democratic dynasty, presented himself as independent-minded and neighborly, vowing early that he would not support Ms. Pelosi to lead House Democrats and playing down his connections to his national party. He echoed traditional Democratic themes about union rights and economic fairness, but took a more conservative position on the hot-button issue of guns.

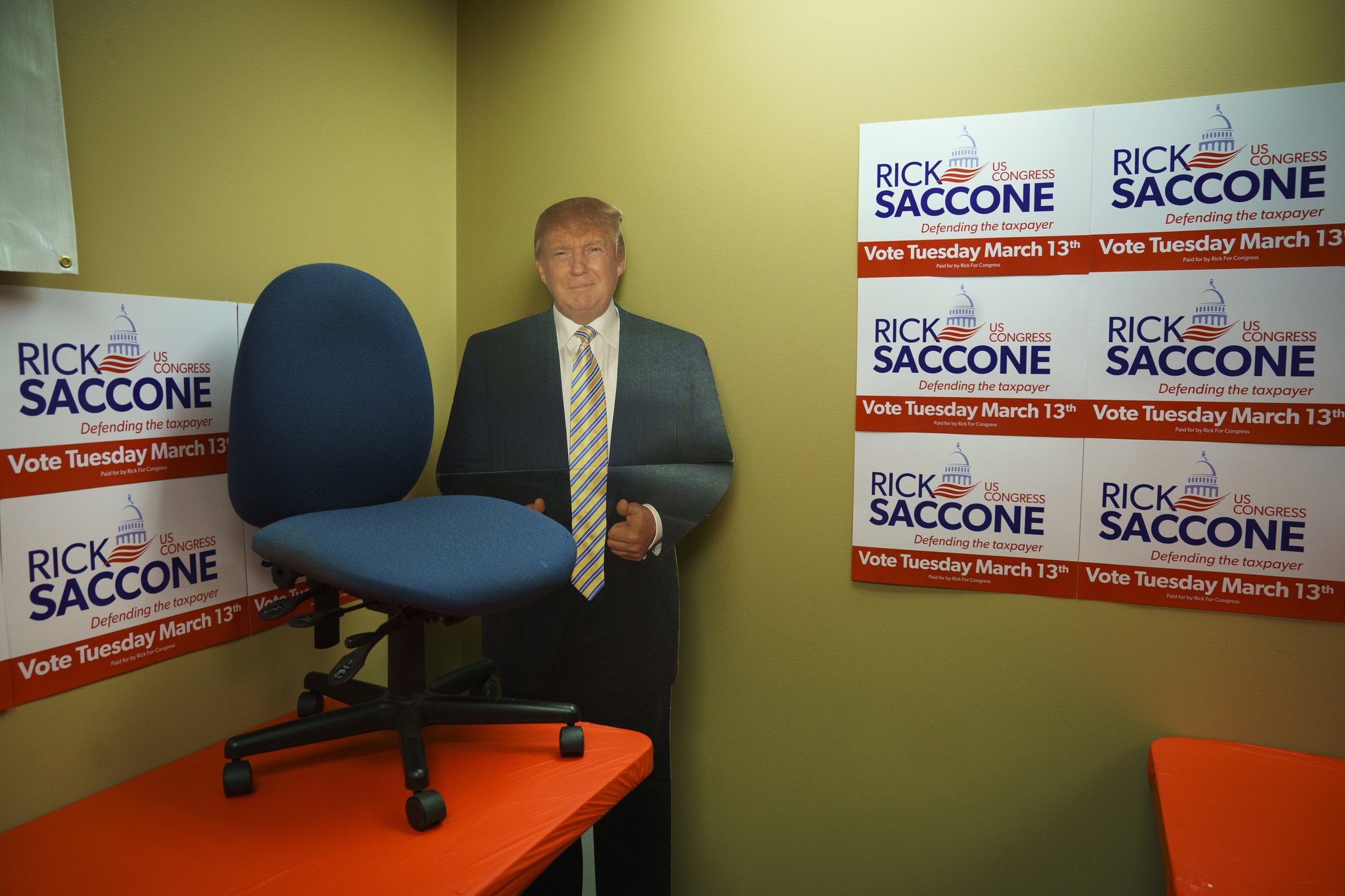

Credit

Drew Angerer/Getty Images

Throughout the race, Mr. Lamb said he welcomed support from people who voted for Mr. Trump, and he saved his most blunt criticism for Mr. Ryan, highlighting the speaker’s ambitions to overhaul Social Security and Medicare.

Mr. Lamb’s approach could become a template for a cluster of more moderate Democrats contesting conservative-leaning seats, in states like Arkansas, Kansas and Utah. Democrats in Washington have focused chiefly on Republican-held seats in the upscale suburbs where Mr. Trump is most intensely disliked.

But they are hungry for gains across the political map, and in red areas they have encouraged candidates to put local imperatives above fealty to the national party, even tolerating outright disavowals of Ms. Pelosi.

Representative Cheri Bustos of Illinois, a Democrat who represents a farm and manufacturing district Mr. Trump narrowly carried, said the party’s recruits should feel free to oppose Ms. Pelosi if they choose. She noted that she was helping one such anti-Pelosi candidate, Paul Davis of Kansas, who was in Washington this week raising money.

“If they want somebody else to be a leader, then they ought to express that,” Ms. Bustos said. “I don’t have a problem with that.”

Representative Mike Doyle of Pennsylvania, a veteran Democrat from a neighboring district, said Mr. Lamb had benefited from “buyer’s remorse” among Trump supporters and had wisely tailored his message to the conservative-leaning area.

“This guy has made a lot of promises that aren’t being kept,” Mr. Doyle said of the president.

On the Republican side, Mr. Saccone, 60, campaigned chiefly as a stand-in for Mr. Trump, endorsing the president’s agenda from top to bottom. He campaigned extensively with Mr. Trump and members of his administration and relied heavily on campaign spending from outside Republican groups that attempted to make Ms. Pelosi a central voting issue. Conservative outside groups also sought to promote the tax cuts recently enacted by the party, but found that message had little effect.

Yet the Republicans’ all-hands rescue mission was not enough to salvage Mr. Saccone’s candidacy. Mr. Saccone has not conceded and Republicans have indicated they may challenge the results through litigation, a long-shot strategy.

Pennsylvania Special Election Results: Lamb Wins 18th Congressional District

See full results and maps of the Pennsylvania special election.

In a meeting with House Republicans on Wednesday morning, Representative Steve Stivers of Ohio, who leads the party’s campaign committee, described the race as “too close to call,” according to a person who heard his presentation.

But Mr. Ryan and Mr. Stivers also called the election a “wake-up call” for Republican lawmakers, telling them that they could not afford to fall behind on fund-raising, as Mr. Saccone did.

Mr. Lamb raised $3.9 million and spent $3 million, compared with Mr. Saccone’s $900,000 raised and $600,000 spent as of Feb. 21. But Republican outside groups swamped the district. Between conservative “super PACs” and the National Republican Congressional Committee, Mr. Saccone had more than $14 million spent on his behalf.

Mr. Lamb got just over $2 million.

As Republican lawmakers spilled out of their morning conference meeting, few seemed willing to come to grips with how much Mr. Trump is energizing Democrats and turning off independent voters. Some of them even argued that Mr. Saccone had managed to make the race close only thanks to the president’s rally in the district on Saturday.

“The president came in and helped close this race and got it to where it is right now,” said Mr. Ryan.

Others in the conference, however, talked more openly about the political difficulties of breaking with Mr. Trump.

“There is no benefit from running away from the president,” said Representative Patrick T. McHenry of North Carolina, a member of his party’s leadership, noting that Republican candidates need core conservative voters, a constituency that still backs the president, to show up.

“It doesn’t get them the same thing as Lamb opposing Pelosi,” Mr. McHenry said.

Even Mr. Stivers, who has the task of re-electing a contingent of lawmakers from districts that backed Hillary Clinton, declined to say Republicans should feel free to break from Mr. Trump.

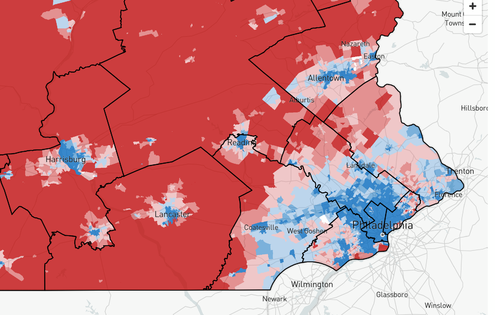

The New Pennsylvania Congressional Map, District by District

Democrats couldn’t have asked for much more from the new map.

“I am not going to tell anybody to be against the president,” he said.

But turnout levels in the district’s suburban precincts proved crucial for Mr. Lamb, and a handful of Republican House veterans conceded this broader vulnerability.

“We know that’s probably where the president’s appeal is the weakest,” said Representative Tom Cole of Oklahoma, a longtime party strategist, adding: “It’s a pattern we’ve seen throughout.”

But he argued that Mr. Trump’s unpopularity in high-income areas would be less of a drag on incumbents who had their own identity and were steeled for difficult races.

Yet even as most Republicans pinned the blame on Mr. Saccone’s fund-raising weakness or held up Mr. Lamb’s willingness to oppose Ms. Pelosi, refusing to fault Mr. Trump, one retiring lawmaker was more blunt.

“Denial isn’t just a river in Egypt,” said Representative Charlie Dent of Pennsylvania, a frequent critic of the president. “I’ve been through wave elections before.”

Democrats were buoyant at Mr. Lamb’s victory, viewing his upset as both a harbinger of a November wave and perhaps a sign that the party had overcome some of the most stinging Republican attack lines of the Obama years. Polling in both parties found Ms. Pelosi widely disliked among voters in the district, but the Republican ads featuring her apparently failed to disqualify Mr. Lamb.

Mayor Bill Peduto of Pittsburgh, a Democrat, said Mr. Lamb’s campaign showed that the Republicans’ anti-Pelosi playbook had limitations. The race, he said, should embolden Democrats to contest difficult districts in the Midwest with an economic message that appeals to elements of Mr. Trump’s base.

“Conor Lamb was talking about redevelopment and economic growth, and the Republicans were talking about Nancy Pelosi,” Mr. Peduto said. “It’s like they couldn’t help themselves.”

Credit

Win Mcnamee/Getty Images

Mr. Peduto urged the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, the electioneering vehicle for House Democrats, to expand its target list in the Trump-aligned Midwest.

“Look through the Rust Belt, in areas that used to be blue,” Mr. Peduto said. “If you’re in a congressional district that’s eight, 10 or 12 points carried by Trump, I would hope that the D.C.C.C. is now putting that in the target.”

To the extent that Democrats attempt further incursions into Trump country, it may test their party’s willingness to tolerate Lamb-like deviation on matters like gun control, and perhaps more widespread rejection of Ms. Pelosi.

Democrats in Washington have already faced criticism from liberal activists for intervening in primary elections, in states like Texas and California, to promote candidates that they view as more electable. Putting forward a slate of moderates in Republican areas could prove more controversial than boosting just one in a special election.

Up to this point, however, Democratic leaders and their campaign tacticians have taken a just-win approach, encouraging candidates to attack Mr. Ryan but taking a far more permissive view of party loyalty than their Republican counterparts.

Clarke Tucker, a Democratic state legislator in Arkansas who is challenging Representative French Hill, a Republican, said on Wednesday that he took Mr. Lamb’s victory as a validation of a throw-the-bums-out message he planned to deliver in his own race. Campaigning in a seat that comprises Little Rock and its suburbs, Mr. Tucker said he seldom spoke about Mr. Trump and announced up front that he would not back Ms. Pelosi.

Mr. Tucker, who was aggressively recruited by the D.C.C.C., said that he had told Democrats in Washington that he was “very frustrated with the leadership of the House in both parties” and that no one attempted to dissuade him from delivering that message.

“That district is a lot like the one I’m running in,” Mr. Tucker said of Mr. Lamb’s seat. “I think voters are interested in changing the leadership in Washington.”

Continue reading the main story

Powered by WPeMatico