A major moment will come in the 2018 midterm elections: Some students will be eligible to vote in November, and have vowed to make gun laws a central issue. Many more hope to organize networks and lay groundwork to vent their frustration — about pervasive school violence, and an unjust political system they view as enabling it — in the next vote for president in 2020.

His Brother Was Shot in Chicago. He’s Marching With Students From Parkland.

Ke’Shon Newman’s brother was shot nine times on Chicago’s South Side, where gun violence is a daily threat. Now, Ke’Shon is heading to Washington to march with high school students from Parkland, Fla.

Whether the students of the post-Parkland movement become a disruptive force depends, in large part, on if they stay organized and register to vote. There is a big practical difference between tuning into politics and actually voting, political strategists and organizers say, and young people often vote at lower rates than older ones, especially in midterm elections.

Page Gardner, president of Women’s Voices Women Vote Action Fund, a Democratic-aligned group that focuses on mobilizing young people, minorities and single women, said the big question was whether teenagers’ activism would translate into votes. The gun issue, she said, had become a focal point for young people who are “just fed up” with the way government works now.

“They do think the system is rigged; this is just an example of it,” Ms. Gardner said of the gun issue. “They want to change it. Whether or not they register and vote to change it, is obviously the $64 million question.”

The students have come of age during a time of political tumult — starting with President Trump’s election and erupting in a new and more focused way with last month’s school shooting. Having already reignited the political debate around guns, they believe they have the potential to bend the ideological and partisan lines of American politics more decisively as they join the electorate.

Lane Murdock, 15, a high school student in Connecticut who is organizing a wave of school-walkout protests on April 20, said the combination of the gun massacres and Mr. Trump’s surprise win had jarred her out of political complacency.

“We were raised to let the adults do the work,” said Ms. Murdock, who is traveling to Washington to join the march there. “When I was growing up and Obama was president, I didn’t pay much attention to politics.”

She called Mr. Trump’s election a turning point: “I think kids are frustrated that they really couldn’t have a say.”

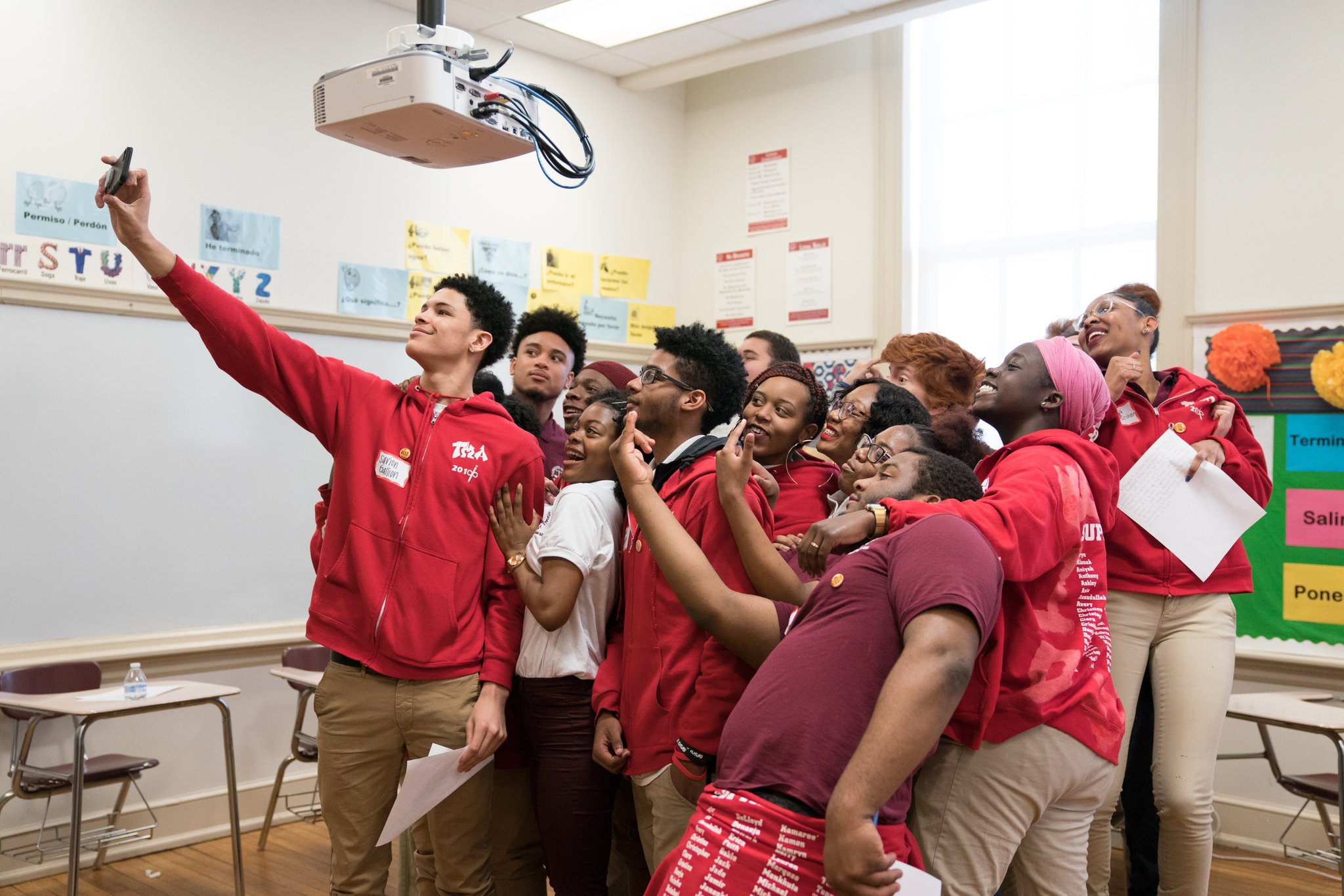

A number of the most prominent young activists from Parkland have already become familiar faces in Washington, and several arrived in the city early on Thursday to meet with students at Thurgood Marshall Academy, a school in Anacostia, a predominantly African-American neighborhood, to discuss gun violence.

Credit

Erin Schaff for The New York Times

Credit

Erin Schaff for The New York Times

Senator Chris Murphy, a Connecticut Democrat who has been meeting regularly with high school-age activists, said they stood out from other groups in their scorn for the political status quo. Mr. Murphy, who became a fierce advocate for gun control after the murder of 20 children in a 2012 mass shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Conn., said he had urged the students to dig in for a long fight, on a historic scale — “like the Civil Rights movement or the anti-Vietnam War movement.”

“These kids are impatient,” said Mr. Murphy, who at 44 is one of the Senate’s youngest members. “This is a generation that is used to demanding immediate gratification, and they want it politically, too.”

The March for Our Lives is likely to echo other mass demonstrations that have sprung up since Mr. Trump’s election. Like the Women’s March, it is to be anchored in Washington with speeches from students from around the country, and complemented by satellite rallies in cities and towns as large as Los Angeles and as small as Pinedale, Wyo.

The National Park Service has approved a permit for the Washington march that estimates 500,000 people could attend, which would make it one of the most impressive displays of collective political will since the last presidential election — and the only one in which many or most of the participants have never been able to vote.

Marchers like Madison Leal, however, are aching to start.

Ms. Leal, 16, a student from Stoneman Douglas, said she would hold a sign at the march bearing 17 blood-red hands and the message: “How many more?” If elected officials do not act, Ms. Leal said, “I’m going to vote them out of office.”

“And so is my entire generation,” she added. “And they’ll be sorry then.”

Credit

Erin Schaff for The New York Times

Among some participants, the determination to defy an indifferent political system mingles with a persistent fear of disappointment. Dantrell Blake, 21, who was shot as a teenager in Chicago and plans to march in Washington, said he hopes to draw attention to gun violence in his hometown but knows that politicians could ignore the message. The mostly black victims of gun violence in Chicago, he said, had not drawn the attention of politicians the way the Parkland shooting did.

“It’s still rigged and they’re still going to do what they want,” Mr. Blake said of elected officials.

Those competing impulses — the drive toward political confrontation, entwined with skepticism that government will accommodate them — may come to define these students as voters. As a group, they combine liberal social beliefs with an intensely wary view of the existing political and economic order, opinion polls have found. While young people are not uniformly Democratic-leaning or supportive of gun regulation, they are well to the left of the middle in their views. They have moved further toward Democrats since Mr. Trump’s election.

Nearly three-fifths of millennial voters — a group slightly older than the high school-age marchers — identify as Democrats, according to a Pew Research Center study. That figure is much higher among women and minorities.

Conservative supporters of gun rights have watched the teenagers’ mounting activism with concern and skepticism. They have organized competing rallies this weekend in places that include Salt Lake City and Helena, Mont., but Bryan Melchior, 45, a Utah gun-rights activist, said he sees the “gun community becoming more of a minority.”

Mr. Melchior, who has been organizing a march in Salt Lake City, questioned the staying power of the Parkland movement.

“It’s not going to change anything about our laws,” Mr. Melchior said of the march on Washington. “What I see is children that are just plain confused.”

John Della Volpe, a pollster who studies young people’s political views for the Harvard Kennedy School’s Institute of Politics, said the gun issue was part of a larger array of social views that define the next wave of voters. While young people are largely liberal, he said they were united chiefly by their dissatisfaction with the existing political system.

“I think that’s what we’re seeing in this movement, in a raw form,” said Mr. Della Volpe, who met this week with some of the Stoneman Douglas activists.

And at least some of the students marching this weekend have already taken steps toward becoming voters.

In Colorado, Rachel Hill, 16, a junior at Columbine High School, the site of a deadly 1999 attack, said she came from a politically mixed family but when she recently signed up to vote — under a Colorado law allowing teenagers to register early — she had identified herself as a Democrat. Ms. Hill said guns were part of the reason, but so were issues like immigration, abortion and gay and transgender rights.

Ms. Hill, who led a walkout at her school to protest gun violence this month, said she plans to march at a rally at the Colorado capitol this weekend. And her aspirations have swerved toward politics for the long term, too: while she once dreamed of becoming an author or an archaeologist, Ms. Hill now hopes to be a member of Congress or an ambassador.

“I thought, well, Trump,” she said. “If he can get into politics and if he can get elected, why can’t I?”

An earlier version of a caption with this article mischaracterized the rally at Thurgood Marshall Academy. Alfonso Calderon and Alex Wind were waiting to join a rally for gun control, not against it.

Continue reading the main story

Powered by WPeMatico